My age, my predatory beast—

who will look you in the eye

and with their own blood mend

the centuries’ smashed-up vertebrae?– Osip Mandelstam

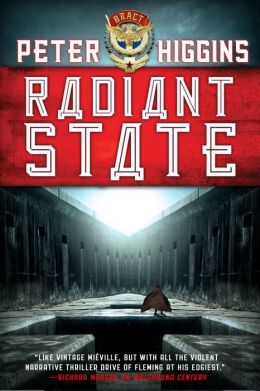

Radiant State is Peter Higgins’ third novel, the unexpectedly mesmerising conclusion to his Vlast trilogy (begun in Wolfhound Century and continued in Truth and Fear). “Unexpectedly mesmerising” because while the previous volumes were lyrical, difficult to categorise entries in the fantasy landscape, Radiant State defies categorisation entirely; situating itself at a literary crossroads where myth and modernity, fantasy and science fiction meet and overlap.

The atomic conflagrations at the conclusion of Truth and Fear have ushered in a new world order. Former terrorist Josef Kantor has erased all trace of his past. He is now Osip Rizhin, Papa Rizhin, supreme leader of the New Vlast. And the New Vlast is going to space on engines of atomic fire: the New Vlast will conquer the stars. The price of progress is the cannibalisation of a nation, totalitarianism, starvation, labour camps consuming the population in the engines of industry. The New Vlast’s vision is Josef Kantor’s vision, and Kantor’s vision doesn’t allow for either failure or retreat.

Six years have passed for Vissarion Lom since the events of Truth and Fear. For Maroussia Shaumian, within the forest, containing the Pollandore, very little time has passed at all. She holds the forest closed, trapping the living angel away from the world of the Vlast—starving it out. But as long as Kantor survives—as long as Kantor’s vision survives—the forest remains under threat. The angel remains a danger. The world remains in danger. Maroussia manages to get a message to Lom: “Stop Kantor… Ruin this world he has created.”

And so Lom sets out to finish what he began: to bring Josef Kantor down.

If that were the whole of Radiant State’s narrative, it would be a simple, straightforward novel. But it isn’t, for the political thriller aspect is almost a sideline, a by-product, to Higgins’ endeavour. What he does, from character to character and scene to scene, is break open the world he has made, show it in all its strangenesses: places where time runs slow and the dead walk, elegiac by a lakeside; the town in the hungry starving lands in the middle of the Vlast where the last poets and philosophers of the old regime gather huddled together in exile; the great furnace of scientific progress that propels the Vlast Universal Vessel Proof of Concept skywards; the empty shadows of the deserted Lodka. Elena Cornelius, sniper and mother, teaching her broken and badly-healed fingers to load her rifle again for a single shot at Papa Rizhin; Yeva Cornelius, her younger daughter, whose months of refuge in a quiet village have been five and a half years in the wider Vlast; Engineer-Technician 2nd-Class Mikkala Avril, dedicated to the visions of the future unfolding in front of her on wings of nuclear fire; Maroussia Shaumian, within the forest and containing the forest within herself; and Vissarion Lom, dogged, hopeful, no longer quite entirely human—if he ever was.

Radiant State is conscious of itself as literature. It doesn’t want you to lose sight of it as a made thing: instead, it uses style and register to direct your attention. Sometimes to mislead. Sometimes to emphasise. Often to highlight the mutability and the strangeness of its magic and its machines: to subtly layer in questions of what it means to be human and when does human become something else, to challenge the costs and myths of progress.

It is explicitly influenced by 20th-century Russia—or perhaps it might be more accurate to say, by the received image of late-19th- and 20th-century Russia. The epigraphs at each chapter head, most of them from Russian poets, thinkers, and politicians (but mostly poets), draw unsubtle attention to this influence, so that we are always reading the text as though through a prism of knowledge, looking for correspondences—or I was. (Not that I know enough about Russian history and literature to see anything but the grossest of allusions.)

With Radiant State, it becomes clear that Peter Higgins is working with similar mythic material to China Miéville (in some of his work) and Max Gladstone: the mythos that forms the most visible substrate in his work are the myths of modernity and the fantasies of progress. (I was remind, somewhat, of the mood of Michael Swanwick’s The Iron Dragon’s Daughter, though Higgins lays out the hope of change in his dystopia: the same gloomy darkness overlays the mixing of magic and mechanism.) The king is dead! Now shall progress reign… Both Higgins and Gladstone use magic in their worldbuilding to make concrete metaphors for thinking about human interaction with our modern worlds, and our relationship to power and the memory of what has gone before—though Higgins uses a more self-consciously “literary” prose register, and his work has, overall, a darker tone.

Not everyone will enjoy Radiant State as a conclusion to the trilogy, but if you’ve enjoyed Higgins’ work thus far, it’s well worth the ride. I recommend it—and I’m deeply interested in seeing what Higgins does for an encore.

Radiant State is available now in the US from Orbit, and publishes May 21st in the UK from Gollancz.

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads books. Her blog. Her Twitter.